The sick returned traveller

Volume 11, Issue 1 January 2016 (download full article in pdf)

Editorial note:

With increasing international travel, awareness and knowledge on the microbiology aspects of the returning traveller is essential, in order for timely diagnosis of infectious diseases acquired abroad and for administration of effective clinical management and public health control measures. In this issue of the Topical Update, Dr. Samson Wong presents a synopsis of the conditions associated with the returned traveller, which will be of practical application to any medical professional. We welcome any feedback or suggestion. Please direct them to Dr. Janice Lo (e-mail: janicelo@dh.gov.hk), Education Committee, The Hong Kong College of Pathologists. Opinions expressed are those of the authors or named individuals, and are not necessarily those of the Hong Kong College of Pathologists.

Dr. Samson SY WONG

Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Introduction

The number of international travellers has been increasing over the past 20 years. In 1995, there were 530 million international arrivals; this figure increased to 1,138 million in 2014 [1]. This rising trend has only been punctuated in 2003 and 2009, coinciding with two infectious disease epidemics, SARS and pandemic influenza, respectively. With the unprecedented volume, speed, and reach of international travel comes an increasing number of patients who developed travel-related health issues. About 15–64% international travellers may develop health problems during their travel [2–5]. The risk depends on the duration of travel, destination, behaviour of the travellers, and the use of prophylactic measures. In most studies, gastrointestinal (usually in the form of travellers’ diarrhoea) and respiratory illnesses are the commonest complaints, followed by skin problems, fever, and other conditions such as altitude sickness, envenoming, accidents and injuries. In this article, we shall focus on the concerns and precautions in the laboratory diagnosis of some important infections in the returned travellers.

Spectrum of infections and approach to the sick returned traveller

The spectrum of travel-related infections is diverse. A large body of information is available from individual centres and from GeoSentinel which consists of 63 travel clinics in 29 countries on 6 continents (http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ page/geosentinel. Accessed on 2 December 2015). However, similar data are lacking in Hong Kong, and one should note that the prevalence of different infections in the literature may not be applicable locally because of differences in the adoption of prophylactic measures and habits of travel. Data from the more recent GeoSentinel surveillance are consistent with earlier studies in that the commonest illnesses in returned travellers affected the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, skin, or presented as fever or systemic illnesses (Table 1) [6–9]. Fever is a common manifestation in such patients, which may occur as an undifferentiated febrile illness or be associated with specific symptoms such as rash, arthritis/arthralgia, or other localizing symptoms. The presence of localizing signs and symptoms helps to narrow the differential diagnoses. Most studies in the literature described malaria as one of the commonest causes of fever, followed by dengue in the more recent series (Table 2). Although malaria is certainly a diagnosis not to be missed, it is not the commonest aetiology of fever in returned travellers in Hong Kong. For example, in 2014, 23 cases of malaria and 112 cases of dengue were notified to the Department of Health [10]. Given that both diseases are primarily imported from endemic countries, dengue would be commoner as a cause of fever in the travellers in Hong Kong.

The clinical approach should always begin with a thorough history including a detailed itinerary (with stopovers), potential exposure history, and prophylactic measures. Despite the long list of differential diagnoses to each clinical syndrome, the most likely causes can often be suggested by the geographical areas visited, the likely incubation period of the disease, and the relevant exposure history. Some important infections associated with specific exposures are listed in Table 3. Subsequent choice of organ imaging and laboratory investigations is guided by the most likely diagnosis. It is important that after the initial assessment, one must not miss conditions that are clinically severe and potentially treatable, as well as those that have a high risk of hospital or community transmission. Severe infections must be investigated and treated urgently, such as sepsis, severe malaria, haemorrhagic fevers, and central nervous system infections. Examples of diseases that require prompt infection control precautions include viral haemorrhagic fevers, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), avian influenza and infections caused by other novel influenza viruses.

Important clinical syndromes and laboratory investigations

Malaria

Malaria must always be considered as a potential cause of fever occurring in anyone who develops fever seven days after travelling to an endemic area [11]. Missing a case of malaria, especially falciparum malaria, can lead to serious and often fatal outcomes which in turn, may lead to medicolegal litigations. There are no pathognomonic clinical signs and symptoms of malaria. Patients are sometimes erroneously diagnosed to have influenza or gastroenteritis initially because of the non-specific clinical symptoms [12–15]. The textbook description of periodic fever is only present in 8–23% of malaria patients [12, 13]. Appropriate laboratory testing must be performed in any patient with a compatible travel history.

The diagnosis of malaria is conventionally made by examination of the thin and thick blood films. The four species of human Plasmodium, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. falciparum are distinguished morphologically. In the past decade, the simian malaria P. knowlesi has emerged as an important cause of human malaria in some Southeast Asian foci, especially in Malaysian Borneo. P. knowlesi infection of travellers has been well reported. The difficulty with P. knowlesi is that its morphology closely resembles other human plasmodia, especially P. malariae. Definitive speciation can generally be made using molecular techniques [16]. Quantification of the level of parasitaemia is essential for falciparum malaria both upon initial diagnosis and serial examination of the blood smear because the level of parasitaemia carries prognostic significance and failure to reduce the level of parasitaemia after antimalarial treatment could signify drug resistance.

Any positive blood smear results must be conveyed to the attending clinician immediately. This is especially critical for P. falciparum which is a medical emergency in the non-immune travellers. It is important to remember that one single negative blood smear cannot exclude malaria. It is generally recommended that in patients with a negative blood smear but with a high clinical suspicion for malaria, at least three blood smears must be repeated over 48 hours to exclude the diagnosis [17–19]. Alternatives to microscopic diagnosis of malaria include antigen detection and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) from peripheral blood. Immunochromatographic antigen detection kits are widely accepted as a form of rapid diagnostic test [20]. These are particularly useful as a form of point-of-care testing and in situations where experienced microscopists are not available. The major drawbacks include the limited sensitivity in patients with low level parasitaemia and their inability to differentiate all four species of human plasmodia. Speciation is clinically essential because P. vivax and P. ovale infections require radical cure with primaquine. NAAT is currently the most sensitive method for detection of bloodborne parasites and mixed infections, and also allows definitive speciation in problematic cases, including P. knowlesi infection [21]. Availability is, however, currently limited to a few centres and the turnaround time is often too long for routine diagnostic purposes.

Arboviruses

The arthropod-borne viruses are fast becoming some of the most important causes of emerging and re-emerging infectious disease outbreaks in tropical and subtropical countries. This is contributed by the global climate and environmental changes, as well as the geographic spread of the vectors, especially mosquitoes. There is a long list of arboviruses, many of which belong to the families of Togaviridae (mosquito-borne; e.g. Chikungunya, Ross River, Eastern, Western, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses), Flaviviridae (e.g. mosquito-borne dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, Zika, Murray Valley encephalitis viruses; tick-borne encephalitis virus), and Bunyaviridae (e.g. mosquito-borne Rift Valley fever virus; tick-borne Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus; sandfly-borne Toscana and sandfly fever viruses) [22].

The global incidence and geographical extent of dengue have been growing over the past five decades with regular outbreaks in different parts of the world [23]. The most recent outbreak is the ongoing epidemic (at the time of writing) in Taiwan, with 39,350 indigenous cases in 2015 (as of 1 December 2015) [24]. This is also the commonest notifiable arbovirus infection in Hong Kong with occasional local transmissions. Dengue is a relatively common cause of fever in returned travellers, causing 2–16.5% of the cases [25]. The disease is traditionally classified into uncomplicated dengue fever, dengue haemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome. The last two entities are usually associated with secondary infections due to serotypes of the virus that are different from the one causing the first episode of infection. Since 2009, the World Health Organization re-classified the disease into dengue fever and severe dengue, the latter being characterized by severe plasma leakage, bleeding, and organ impairment [23].

Chikungunya is another arbovirus infection that has gained much attention in the past decade since an outbreak started in Kenya in 2004, with subsequent spread to the Indian Ocean islands till 2006, and infected over one third of the population in La Réunion [26]. Outbreaks of this togavirus have been repeatedly reported in recent years, affecting countries in Asia, Africa, the Pacific islands, Central and South Americas. Likewise, infections due to Zika virus received little attention until it caused large outbreaks in the Yap State of Federated States of Micronesia in 2007 and the French Polynesia in 2013 [27]. Zika virus is endemic in various countries in Africa, Asia, Oceania, the Pacific islands, and since 2014, in Latin and South America (especially Brazil, but also Chile, Colombia, Suriname, Jamaica, and Dominican Republic) [27, 28].

Given the large number of arboviruses, the choice of diagnostic tests should be guided by the geographical area(s) of travel and clinical syndrome. Arbovirus infections commonly manifest as systemic febrile illnesses with or without rash, arthralgia or arthritis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis, or viral haemorrhagic fever (Table 4) [22, 29]. Many of the viruses are geographically restricted. Requests for investigations against specific viruses should be guided by the travel history and clinical manifestations. Viral culture can be performed for some viruses, but this is generally not the test of choice in most circumstances. Viral serology, preferably with paired sera for antibody testing, is one of the options of investigation, though the availability of serological tests for rarer infections is limited. Antibody testing is readily available for arboviruses such as dengue, Japanese encephalitis, and chikungunya. It should be remembered that antibody testing may be negative in the very early stage of disease, and a second serum should always be obtained. The paired antibody profile in dengue patients can also help to differentiate primary from secondary infections. Another drawback in viral antibody testing is the potential cross reactivity between different viruses, which is common among flaviviruses for example. In terms of dengue diagnostics, detection of the viral NS1 antigen in serum is superior to IgM antibody detection in the first two to three days after disease onset, a window period where IgM is often negative [30]. A combined NS1 antigenaemia and IgM antibody testing is currently a common approach to initial diagnosis of dengue. The use of NS1 lateral flow assay kits may even allow point-of-care testing for dengue, and if the roles of urine and saliva NS1 are substantiated by further studies, this will facilitate the diagnosis of dengue in resource-limited settings [31, 32]. NAAT is another option for early diagnosis of dengue which also permits detection of co-infection by different serotypes (and with other arboviruses) and genotyping of the infecting viral strains [33–35]. Antibody detection (IgM and IgG) and NAAT can also be used for the diagnosis of chikungunya and Japanese encephalitis. Consultation with clinical virologists should be made in order to choose the most appropriate tests, especially when unusual viral agents are suspected.

Enteric syndromes

Important enteric infections encountered in returned travellers include travellers’ diarrhoea, enteric fever, and amoebiasis. Travellers’ diarrhoea is the commonest travel-related infection, affecting 10–40% of individuals travelling from developed to developing countries [36]. It is most often a bacterial infection caused by various diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (especially enterotoxigenic strains) and other enteorpathogens such as Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Other pathogens include viruses (especially Norovirus, classically associated with passenger ships) and parasites (such as Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Cyclospora) as well as mixed infections. Most cases of travellers’ diarrhoea are self-limiting. Specific microbiological investigations may not be necessary in milder cases, but should be considered in those with more severe manifestations (such as fever, dysentery, bloody diarrhoea, cholera-like symptoms), persistent symptoms, or in immunocompromised individuals [36]. Specific requests for viral agents (antigen detection or NAAT for Rotavirus, NAAT for Norovirus) or special concentration and staining for protozoa (e.g. modified acid-fast staining for Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, and Cystoisospora) are necessary if routine bacterial cultures are unremarkable.

Enteric fever in Hong Kong can be indigenous or imported. This is most commonly due to typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, caused by Salmonella enterica Typhi and Paratyphi (A, B, C) respectively. Laboratory diagnosis of typhoid and paratyphoid fevers remains problematic. A positive culture from blood or other specimens (stool, urine, bone marrow) provides the definitive diagnosis, though this is not always possible due to the kinetics of bacterial shedding and circulation at different sites or prior antibiotic usage, and that bone marrow culture (the most sensitive type of specimen) is not routinely performed in this setting. Serological testing has been an important adjunct to diagnosis. Unfortunately, the widely available Widal’s test is neither sensitive nor specific for this purpose, especially when only a single serum is tested. Newer serological assays such TUBEX TFTM (IDL Biotech, Sweden) and TyphidotTM (Reszon Diagnostics, Malaysia) have improvements over the Widal’s test, but their performance in the field has not been encouraging [37, 38]. Perhaps more promising in the future is the detection of Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi in peripheral blood by NAAT [39]. This approach has the additional benefit of detecting other circulating pathogens as a panel (e.g. using multiplex PCR) for systemic febrile illnesses in travellers, such as Plasmodium, Babesia, Rickettsia, Orientia, and other pathogenic bacteria and viruses [40].

Entamoeba histolytica infection most often manifests as amoebic colitis; extraintestinal amoebiasis is less frequently seen and the usual presentation is amoebic liver abscess. Intestinal infection is mainly diagnosed by faecal microscopy. As in the case of other enteric parasites, multiple stool samples (usually at least three) should be examined. E. histolytica is morphologically identical to at least three other species of Entamoeba, viz. E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, and E. bangladeshi. Definitive identification is best achieved by molecular methods. Antigen detection assays are viable alternatives for the detection E. histolytica in stool [41]. Some of these kits can concurrently detect other enteric protozoa such as Giardia intestinalis and Cryptosporidium. Not all of the antigen detection assays, however, are able to differentiate E. histolytica and E. dispar. Microscopy is less useful in amoebic liver abscesses; amoebae are seen in only 20% or less of liver aspirates [42]. Stool samples of patients with amoebic liver abscesses have positive microscopy for E. histolytica in only 8–44% of the cases [42]. Antibody testing is helpful in the diagnosis of amoebic liver abscess; a positive serology is present in over 95% of the patients [41–43]. The major drawback of serology is that it cannot differentiate active from past infections with E. histolytica, and hence it is less useful for populations in endemic areas.

Other issues

Space does not permit further discussion on other travel-related infections. Two more recent issues may require attention from clinical and laboratory colleagues. Firstly, the transmission of epidemic-prone infectious diseases through travel, and in particular, air travel, has caused much concern in the past few years. Examples include avian influenza and other novel influenza viruses, MERS-CoV (and the SARS-CoV in 2003), Ebola virus and other agents of viral haemorrhagic fevers. Although these are relatively uncommon causes of infection in returned travellers (with the exception of pandemic influenza in 2009), transnational spread of these infections remains a constant threat to non-endemic countries and contingency plans for surveillance, screening, clinical management, infection control, and laboratory diagnostics must be formulated in anticipation [44].

Secondly, the importation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from travellers has emerged as another menace [45–47]. The main microbes of concern include extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. These may be causing active infections or merely colonizing the travellers. Areas with the highest risks are the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Africa [48–51]. Encounters with hospitals or medical facilities abroad could be due to medical problems that appeared during travel or being part of an increasingly popular medical tourism. Admission screening for multidrug-resistant organisms should be considered for patients with recent hospitalization in overseas facilities.

And not just for the microbiologists

Although the majority of tests for infective complications among the returned travellers are performed by the clinical microbiology laboratory, other specialties of clinical pathology may sometimes be involved in the investigation. The commonest scenario is the examination of peripheral blood films by haematology colleagues for malaria parasites. In addition to Plasmodium species, other pathogens that may be seen in the blood films include Babesia spp., Trypanosoma spp. (the African T. brucei gambiense and T. brucei rhodesiense, as well as the American T. cruzi), microfilariae, and the spirochaete bacterium Borrelia spp. The identification of Babesia spp. is sometimes mistaken for Plasmodium spp. because of the presence of intra-erythrocytic ring forms [52]. The travel history, especially when the destination is not a malaria-endemic region, should alert the microscopist to the possibility of babesiosis. Other morphological features that are suggestive of Babesia include the absence of stipplings and malarial pigments, presence of multiple pleomorphic rings within a single erythrocyte, and arrangement of the parasites in a Maltese cross appearance. Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease, is possibly the best-known Borrelia species. However, B. burgdorferi is not normally seen in the peripheral blood smear. When spirochaetes are observed, the possibility of tick-borne or louse-borne relapsing fever should be considered. Tick-borne borrelioses are zoonoses caused by over 30 species of Borrelia and they have a global occurrence. Louse-borne relapsing fever, on the other hand, is restricted to countries in the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan) nowadays. It is caused by Borrelia recurrentis which causes infection in humans only. The significance of louse-borne relapsing fever as a potential re-emerging infection is highlighted by the recent cases reported amongst asylum seekers who travelled to Europe from East Africa [53–56]. Definitive identification of Borrelia species requires molecular testing of the blood sample by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and other targets.

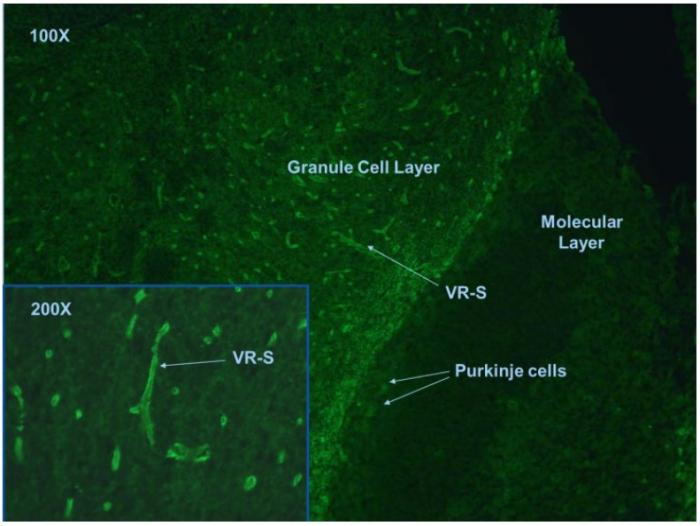

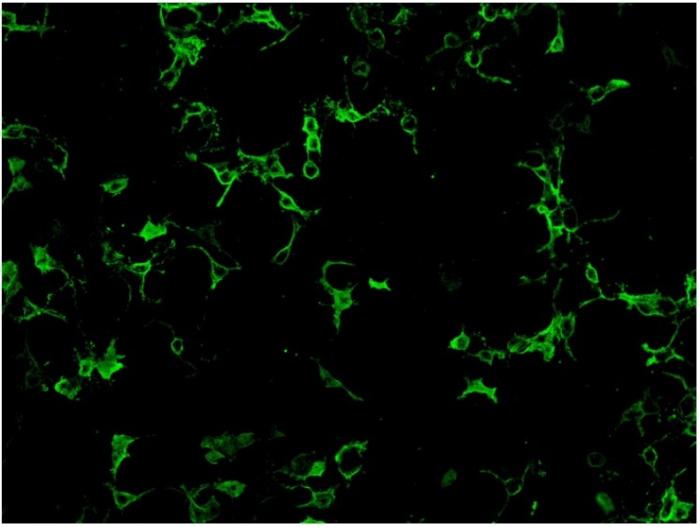

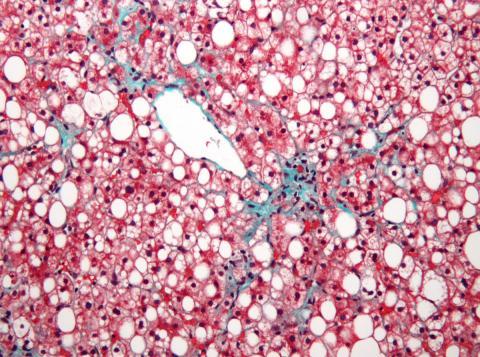

In addition to blood smear examination, the anatomical pathologist may encounter unexpected or unusual infections. Some of these infections may present as subacute or chronic lesions and may be seen in immigrants from foreign countries rather than recent travellers. Examples include colonic or liver biopsies with E. histolytica or Schistosoma; soft tissue or visceral lesions due to larval stages of nematodes (such as dirofilariasis or onchocerciasis) or cestodes (such as sparganosis, cysticercosis); skin biopsy in patients with cutaneous or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis; bone marrow, liver, spleen, or lymph node biopsies in patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Most of these are relatively rare in Hong Kong, but they may spice up our otherwise mundane everyday routines.

References

1 World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Press release No.: 15006, 27 January 2015. Available at: http://media.unwto.org/press-release/2015-01-27/over-11-billion-tourists-travelled-abroad-2014. Accessed on 29 November 2015.

2 Steffen R, Rickenbach M, Wilhelm U, Helminger A, Schär M. Health problems after travel to developing countries. J Infect Dis 1987;156:84–91.

3 Ahlm C, Lundberg S, Fessé K, Wiström J. Health problems and self-medication among Swedish travellers. Scand J Infect Dis 1994;26:711–717.

4 Hill DR. Health problems in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. J Travel Med 2000;7:259–266.

5 Rack J, Wichmann O, Kamara B, Günther M, Cramer J, Schönfeld C, Henning T, Schwarz U, Mühlen M, Weitzel T, Friedrich-Jänicke B, Foroutan B, Jelinek T. Risk and spectrum of diseases in travelers to popular tourist destinations. J Travel Med 2005;12:248–53.

6 Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, Kozarsky P, Freedman DO, Plier DA, Sotir MJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for travel-related disease—GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 2013;62:1–23.

7 Hagmann SH, Han PV, Stauffer WM, Miller AO, Connor BA, Hale DC, Coyle CM, Cahill JD, Marano C, Esposito DH, Kozarsky PE; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Travel-associated disease among US residents visiting US GeoSentinel clinics after return from international travel. Fam Pract 2014;31:678–687.

8 Boggild AK, Geduld J, Libman M, Ward BJ, McCarthy AE, Doyle PW, Ghesquiere W, Vincelette J, Kuhn S, Freedman DO,Kain KC. Travel-acquired infections and illnesses in Canadians: surveillance report from CanTravNet surveillance data, 2009–2011. Open Med 2014;8:e20–32.

9 Leder K, Torresi J, Libman MD, Cramer JP, Castelli F, Schlagenhauf P, Wilder-Smith A, Wilson ME, Keystone JS, Schwartz E, Barnett ED, von Sonnenburg F,Brownstein JS, Cheng AC, Sotir MJ, Esposito DH, Freedman DO; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. GeoSentinel surveillance of illness in returned travelers, 2007–2011. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:456–468.

10 Centre for Health Protection. Number of notifications for notifiable infectious diseases in 2014. Available at http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/data/ 1/10/26/43/2280.html. Accessed on 2 December 2015.

11 Warrell DA. Clinical features of malaria. In: Gilles HM, Warrell DA (eds). Bruce-Chwatt’s Essential Malariology, 3rd ed. London: Arnold; 1993. p 35–49.

12 Brook MG, Bannister BA. The clinical features of imported malaria. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev 1993;3:R28–31.

13 Dorsey G, Gandhi M, Oyugi JH, Rosenthal PJ. Difficulties in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of imported malaria. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2505–2010.

14 Yombi JC, Jonckheere S, Colin G, Van Gompel F, Bigare E, Belkhir L, Vandercam B. Imported malaria in a tertiary hospital in Belgium: epidemiological and clinical analysis. Acta Clin Belg 2013;68:101–106.

15 Cheong HS, Kwon KT, Rhee JY, Ryu SY, Jung DS, Heo ST, Shin SY, Chung DR, Peck KR, Song JH. Imported malaria in Korea: a 13-year experience in a single center. Korean J Parasitol 2009;47:299–302.

16 Antinori S, Galimberti L, Milazzo L, Corbellino M. Plasmodium knowlesi: the emerging zoonotic malaria parasite. Acta Trop 2013;125:191–201.

17 Pasricha JM, Juneja S, Manitta J, Whitehead S, Maxwell E, Goh WK, Pasricha SR, Eisen DP. Is serial testing required to diagnose imported malaria in the era of rapid diagnostic tests? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:20–23.

18 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Treatment of malaria (guidelines for clinicians). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/resources/ pdf/clinicalguidance.pdf. Accessed on 2 December 2015.

19 White NJ. The treatment of malaria. N Engl J Med 1996;335:800–806.

20 Mouatcho JC, Goldring JP. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests: challenges and prospects. J Med Microbiol 2013;62:1491–1505.

21 Wong SS, Fung KS, Chau S, Poon RW, Wong SC, Yuen KY. Molecular diagnosis in clinical parasitology: when and why? Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2014;239:1443–1460.

22 Cleton N, Koopmans M, Reimerink J, Godeke GJ, Reusken C. Come fly with me: review of clinically important arboviruses for global travelers. J Clin Virol 2012;55:191–203.

23 World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 10665/44188/1/9789241547871_eng.pdf. Accessed on 2 December 2015.

24 Centers for Disease Control, R.O.C. (Taiwan). Press release. 1 December 2015. http://www.cdc. gov.tw/english/info.aspx?treeid=bc2d4e89b154059b&nowtreeid=ee0a2987cfba3222&tid=03F130A967838822. Accessed on 2 December 2015.

25 Ratnam I, Leder K, Black J, Torresi J. Dengue fever and international travel. J Travel Med 2013;20:384–393.

26 Burt FJ, Rolph MS, Rulli NE, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. Chikungunya: a re-emerging virus. Lancet 2012;379:662–671.

27 Ioos S, Mallet HP, Leparc Goffart I, Gauthier V, Cardoso T, Herida M. Current Zika virus epidemiology and recent epidemics. Ioos S, Mallet HP, Leparc Goffart I, Gauthier V, Cardoso T, Herida M. Med Mal Infect 2014;44:302–307.

28 World Health Organization. Zika virus outbreaks in the Americas. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2015;90:609–610.

29 Gubler DJ. Human arbovirus infections worldwide. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001;951:13-24.

30 Matheus S, Pham TB, Labeau B, Huong VT, Lacoste V, Deparis X, Marechal V. Kinetics of dengue non-structural protein 1 antigen and IgM and IgA antibodies in capillary blood samples from confirmed dengue patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:438–443.

31 Gan VC, Tan LK, Lye DC, Pok KY, Mok SQ, Chua RC, Leo YS, Ng LC. Diagnosing dengue at the point-of-care: utility of a rapid combined diagnostic kit in Singapore. PLoS One 2014;9:e90037.

32 Korhonen EM, Huhtamo E, Virtala AM, Kantele A, Vapalahti O. Approach to non-invasive sampling in dengue diagnostics: exploring virus and NS1 antigen detection in saliva and urine of travelers with dengue. J Clin Virol 2014;61:353–358.

33 Sudiro TM, Zivny J, Ishiko H, Green S, Vaughn DW, Kalayanarooj S, Nisalak A, Norman JE, Ennis FA, Rothman AL. Analysis of plasma viral RNA levels during acute dengue virus infection using quantitative competitor reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol 2001;63:29–34.

34 Cnops L, Domingo C, Van den Bossche D, Vekens E, Brigou E, Van Esbroeck M. First dengue co-infection in a Belgian traveler returning from Thailand, July 2013. J Clin Virol 2014;61:597–599.

35 Parreira R, Centeno-Lima S, Lopes A, Portugal-Calisto D, Constantino A, Nina J. Dengue virus serotype 4 and chikungunya virus coinfection in a traveller returning from Luanda, Angola, January 2014. Euro Surveill 2014;19. pii: 20730.

36 Steffen R, Hill DR, DuPont HL. Traveler’s diarrhea. A clinical review. JAMA 2015;313(1):71–80.

37 Parry CM, Wijedoru L, Arjyal A, Baker S. The utility of diagnostic tests for enteric fever in endemic locations. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2011;9:711–725.

38 Thriemer K, Ley B, Menten J, Jacobs J, van den Ende J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the performance of two point of care typhoid fever tests, Tubex TF and Typhidot, in endemic countries. PLoS One 2013;8:e81263.

39 Tennant SM, Toema D, Qamar F, Iqbal N, Boyd MA, Marshall JM, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y, Quadri F, Khan A, Aziz F, Ahmad K, Kalam A, Asif E,Qureshi S, Khan E, Zaidi AK, Levine MM. Detection of typhoidal and paratyphoidal Salmonella in blood by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61 Suppl 4:S241–250.

40 Watthanaworawit W, Turner P, Turner C, Tanganuchitcharnchai A, Richards AL, Bourzac KM, Blacksell SD, Nosten F. A prospective evaluation of real-time PCR assays for the detection of Orientia tsutsugamushi and Rickettsia spp. for early diagnosis of rickettsial infections during the acute phase of undifferentiated febrile illness. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;89:308–310.

41 Ali IK. Intestinal amebae. Clin Lab Med 2015;35:393–422.

42 Singh U, Petri Jr WA. Amebas. In: Gillespie S, Pearson RD (eds). Principles and Practice of Clinical Parasitology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. p 197–218.

43 Fotedar R, Stark D, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for Entamoeba species. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:511–532.

44 Wong SS, Wong SC. Ebola virus disease in nonendemic countries. J Formos Med Assoc 2015;114:384–398.

45 Epelboin L, Robert J, Tsyrina-Kouyoumdjian E, Laouira S, Meyssonnier V, Caumes E; MDR-GNB Travel Working Group. High rate of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli carriage and infection in hospitalized returning travelers: a cross-sectional cohort study. J Travel Med 2015;22:292–299.

46 Von Wintersdorff CJ, Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Oude Lashof AM, Hoebe CJ, Savelkoul PH, Wolffs PF. High rates of antimicrobial drug resistance gene acquisition after international travel, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20):649–657.

47 Josseaume J, Verner L, Brady WJ, Duchateau FX. Multidrug-resistant bacteria among patients treated in foreign hospitals: management considerations during medical repatriation. J Travel Med 2013;20:22–28.

48 Vila J. Multidrug-resistant bacteria without borders: role of international trips in the spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Travel Med 2015;22:289–291.

49 Kuenzli E, Jaeger VK, Frei R, Neumayr A, DeCrom S, Haller S, Blum J, Widmer AF, Furrer H, Battegay M, Endimiani A, Hatz C. High colonization rates of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in Swiss travellers to South Asia—a prospective observational multicentre cohort study looking at epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:528.

50 Peirano G, Laupland KB, Gregson DB, Pitout JD. Colonization of returning travelers with CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli. J Travel Med 2011;18:299–303.

51 Freeman JT, McBride SJ, Heffernan H, Bathgate T, Pope C, Ellis-Pegler RB. Community-onset genitourinary tract infection due to CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli among travelers to the Indian subcontinent in New Zealand. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:689–692.

52 Chau C. First reported case of imported babesiosis in Hong Kong. Communicable Disease Watch 2006;3:1–3.

53 Wilting KR, Stienstra Y, Sinha B, Braks M, Cornish D, Grundmann H. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) in asylum seekers from Eritrea, the Netherlands, July 2015. Euro Surveill 2015;20. pii: 21196.

54 Goldenberger D, Claas GJ, Bloch-Infanger C, Breidthardt T, Suter B, Martínez M, Neumayr A, Blaich A, Egli A, Osthoff M. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) in an Eritrean refugee arriving in Switzerland, August 2015. Euro Surveill 2015;20:2–5.

55 Hoch M, Wieser A, Löscher T, Margos G, Pürner F, Zühl J, Seilmaier M, Balzer L, Guggemos W, Rack-Hoch A, von Both U, Hauptvogel K, Schönberger K, Hautmann W, Sing A, Fingerle V. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) diagnosed in 15 refugees from northeast Africa: epidemiology and preventive control measures, Bavaria, Germany, July to October 2015. Euro Surveill 2015;20(42).

56 Lucchini A, Lipani F, Costa C, Scarvaglieri M, Balbiano R, Carosella S, Calcagno A, Audagnotto S, Barbui AM, Brossa S, Ghisetti V, dal Conte I, Caramello P, di Perri G. Louse-borne relapsing fever among east African refugees, Italy, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016. In press. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/2/15-1768_article. Accessed on 28 November 2015.

Table 1. Illnesses in returned international travellers from GeoSentinel surveillance.

|

Country

|

USA [6]

|

USA [7]

|

Canada [8]

|

Global centres [9]

|

|

Years

|

1997–2011

|

2000–2012

|

2009–2011

|

2007–2011

|

|

Number of travellers studied

|

10,032

|

9,624

|

4,365

|

42,173

|

|

Systems involved

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gastrointestinal tract

|

45%

|

58.4%

|

43.7%

|

34.0%

|

|

Respiratory system

|

8%

|

10.8%

|

5.4%

|

10.9%

|

|

Skin

|

12%

|

16.6%

|

14.7%

|

19.5%

|

|

Fever or systemic illness

|

14%

|

18.2%

|

10.8%

|

23.3%

|

|

Neurological system

|

|

|

|

1.7%

|

|

Genito-urinary tract and gynaecological system, sexually-transmitted infections

|

|

|

|

2.9%

|

Table 2. Causes of fever in returned international travellers from GeoSentinel surveillance.

|

Country

|

USA [6]

|

USA [7]

|

Canada [8]

|

Global centres [9]

|

|

Years

|

1997–2011

|

2000–2012

|

2009–2011

|

2007–2011

|

|

Number of patients presenting with fever or systemic illness

|

1802

|

1748

|

675

|

9817

|

|

Diagnoses

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria

|

19.4%

|

27.4%

|

11.9%

|

28.7%

|

|

Dengue

|

11.1%

|

12%

|

7.1%

|

15.0%

|

|

Chikungunya

|

|

|

0.9%

|

1.7%

|

|

Enteric fever

|

|

6.1%

|

4.1%

|

4.8%

|

|

Respiratory tract infections

|

|

|

6.7%

|

|

|

Active tuberculosis

|

|

|

7%

|

|

|

Urinary tract infection

|

|

|

1.5%

|

|

|

Rickettsioses

|

|

4.7%

|

0.7%

|

3.0%

|

|

Leptospirosis

|

|

|

|

0.8%

|

|

Brucellosis

|

|

|

0.9%

|

0.3%

|

|

Hepatitis A and E

|

|

|

|

1.7%

|

|

Acute HIV infection

|

|

|

|

0.9%

|

|

Viral syndrome

|

17.1%

|

18.5%

|

|

|

|

Unspecified febrile illness

|

8.2%

|

|

|

|

|

Epstein-Barr virus infection and infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome

|

4.4%

|

8.7%

|

|

|

Table 3. Exposure history that should raise suspicion to specific infections.

|

Exposure

|

Potential infective complications

|

|

Sex, blood, body fluids, surgical operations, intravenous drug use

|

Hepatitis B and C, HIV infection, syphilis

|

|

Tattoos, body piercing, other body modification procedures

|

Hepatitis B and C, HIV infection, syphilis, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections

|

|

Hospitalization

|

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (colonization or infection)

|

|

Ingestion of raw or undercooked food

|

Various foodborne infections including bacterial and viral gastroenteritis, protozoal and helminth infections, brucellosis, listeriosis, toxoplasmosis, hepatitis A and E

|

|

Soil

|

Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycoses, other endemic mycoses,

cutaneous larva migrans, strongyloidiasis

|

|

Freshwater

|

Schistosomiasis (Katayama fever), leptospirosis

|

|

Arthropod bites

|

Various arthropod-borne infections, such as dengue, chikungunya, Zika virus infection, rickettsioses, relapsing fevers, malaria, babesiosis, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, dirofilariasis

|

|

Dog, bat and other animal bites

|

Rabies, bat rabies, herpes B virus infection, bite wound infections

|

|

Animals and animal products

|

Hantaviruses, Lassa fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fevers, avian influenza, MERS, plague, rat-bite fevers, leptospirosis, Q fever, brucellosis, tularaemia, anthrax, psittacosis.

|

Note that the exact risk of specific infections depends not only on the exposure history, but the geographical location of exposures.

Table 4. Some common arboviruses and their typical clinical syndromes.

|

Common clinical syndromes

|

Common causative agents

|

|

Systemic febrile illness ± rash

|

Dengue virus, West Nile virus, Yellow fever virus, Zika virus, chikungunya virus

|

|

Arthralgia, arthritis ± rash

|

Chikungunya virus, Ross River virus, Barmah Forest virus, dengue virus, West Nile virus, O’nyong’nyong virus

|

|

Encephalitis or meningoencephalitis

|

Japanese encephalitis virus, Murray Valley encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, California encephalitis virus, La Crosse virus, Rift Valley fever virus, Toscana virus, Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus

|

|

Viral haemorrhagic fevers

|

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever virus, yellow fever virus, dengue virus, Kyasanur Forest disease virus, Omsk haemorrhagic fever, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus

|

Note that the clinical syndromes and severity of disease caused by any single arbovirus can vary substantially. For example, many infections can either be subclinical or manifest as undifferentiated fever or produce a fulminant disease, such as viral haemorrhagic fever or meningoencephalitis. The likelihood of various potential pathogens depends on the exact geographical areas involved.